He was one of the 20th century’s most famous American poets and she was a Parisian sex worker. Now previously unpublished letters written by EE Cummings and Marie Louise Lallemand during the first world war reveal for the first time that the pair had been deeply in love.

Cummings is best known for his love poem, i carry your heart with me (i carry it in my heart), written in 1952, which starts with the lines: “i carry your heart with me (i carry it in my heart) i am never without it (anywhere i go you go, my dear; and whatever is done by only me is your doing, my darling)”.

He went on to become an avant-garde poet revered for his pursuit of literary experimentation over style and structure, spelling and punctuation.

The letters, dated 1917, which are held in the Houghton Library, Harvard, reveal that many decades before i carry your heart with me, Cummings was writing privately with the same passion that he went on to become famous for.

In one letter, written from the frontline in France, Cummings told Lallemand: “Darling, Marie Louise, you who are more to me than the scarlet poppies which are mown, more than the yellowing evenings which we see die, more than the silence full of stars, the completely white silence of night, only awaiting dawn, – take the kiss which I give you, that kiss, without value, because it comes from a soul which loves you.”

Lallemand’s letters mirrored his passion for her: “I love you I love you.” But she also feared that he would forget her, just like other men she had encountered: “I have suffered much all my life … It’s always been men; never mind, it makes no difference.”

Alison Rosenblitt, author of a forthcoming Cummings biography, told the Observer that previous research has handled their relationship “very dismissively – inflected, in my view, by prejudices about sex workers”.

She said that the Cummings-Lallemand correspondence tells “a very tender and poignant story”, showing the depth of their love. Cummings wrote to Lallemand in French, composing several drafts, which have survived.

Rosenblitt said: “Throughout his letters to Marie Louise, he says again and again how kind she has been, and how he is cruel. He transmits his own fear that he did not know how to be a lover. But more deeply, his persistent fear that he was cruel held him back from opening himself up fully to her.”

In one letter, Cummings wrote that, if he had hurt her, then he too was hurting: “You say you suffer and that I have never suffered in love. But I also suffer perhaps a little. You are right: I am not worthy to say I have felt that pain. You have said it: nothing is equal to your sufferings. O joyous young girl!”

Rosenblitt said: “Marie Louise’s own unhappiness and anger at her life clearly left Cummings unable to believe that she could be serious in her feelings for him. But he did not retreat.”

As the US prepared to enter the war, Cummings had been shipped out to France after volunteering as an ambulance driver. Having just graduated from Harvard, he went in search of adventure and found it. He was imprisoned for months in a French detention centre, wrongly suspected of treason due to letters written by a friend, a harrowing experience that inspired his first book, The Enormous Room, an autobiographical novel.

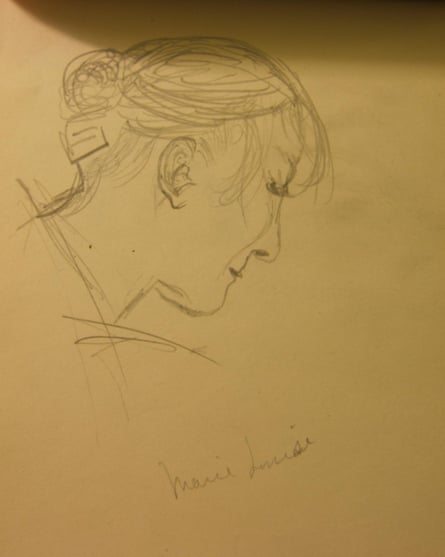

How he first met Lallemand is unknown. But on the back of one of his notebooks, in a woman’s handwriting, is her address, and a time and place for meeting up: “Saturday, noon, Place de la République, at the statue.” Perhaps that was their first date, Rosenblitt suggests, noting that Cummings also drew several sketches of Lallemand in a notebook and in words: “In the only published poem that names her, Cummings slips from thoughts of her to thoughts of the Virgin Mary, ‘Marie Vierge Priez Pour Nous’ (pray for us).”

In her forthcoming biography, The Beauty of Living: EE Cummings in the Great War, Rosenblitt writes of Lallemand: “She has been pushed to the margins because she was a sex worker, and that is wrong. It is an injustice to her, and it is also an injustice to the hundreds of thousands of women who worked as prostitutes during the great war.”

She observes that Lallemand loved poetry, introducing Cummings to the 19th-century French romantic poet Alfred de Musset. On his return to Paris from the front, Cummings searched in vain for her. She had disappeared without trace, perhaps before receiving a final love letter in which he had declared: “If you think, Marie Louise, that I have forgotten the days and nights that we spent together, then you are mistaken.”

The Beauty of Living: EE Cummings in the Great War will be published by WW Norton in August.

i carry your heart with me © 1952, 1980, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust