“Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.” [said the Duchess]

“I think I should understand that better,” Alice said very politely, “if I had it written down: but I can't quite follow it as you say it.”

Chapter IX

Lewis Carroll had a rather poor opinion of American publishing. Initially, he did not want to sell Alice to a market seemingly so uninterested in producing books to his standards. So he had no reservation about sending the rejected sheets from the suppressed 1865 edition, deemed not good enough for the British public, to readers in America. They were published in 1866, with a new title page, by D. Appleton & Co.

Perhaps contributing to Carroll’s dislike of the American book market, American copyright law did not protect foreign authors’ works from unauthorized reproduction; many pirated editions appeared after the 1866 Appleton edition. The first authorized edition to be printed in America was published in 1869 by Lee and Shepard of Boston.

American illustrators, in editions both authorized and pirated, initially drew heavily on Tenniel’s illustrations, but gradually introduced their own styles and American aesthetic into the story.

After suppressing the 1865 first English edition of Alice, Carroll was left with several thousand sets of unbound sheets. New York publisher D. Appleton & Co. purchased the sheets and published them with a new title page in May 1866. Reviews in America were favorable, although little is known about the success of this edition.

On this opening, one can see one of the muddy illustrations that led Tenniel and Carroll to reject this printing for the British market.

The Seaside Library was one of the most successful American publishers of cheap pirated reprints. Its edition of Alice, with poorly-rendered illustrations, sold for twelve cents. This was Carroll’s own copy – he was perhaps monitoring American piracies of his work.

Physician Samuel Gridley Howe created the Boston Line letter tactile alphabet, a precursor to Braille, in 1835, to aid visually-impaired students at the Perkins Institute and Massachusetts School for the Blind. The school published a number of popular nineteenth-century titles in blind-embossed type, including Alice.

This was the first printing of Alice for the blind; a Braille edition followed in 1921.

John Tenniel famously created forty-two illustrations for the first edition of Alice (42 was Carroll’s favorite number); illustrator Harry Rountree filled this edition with 92 watercolors and line drawings.

Hungarian artist Willy Pogány’s illustrations were among the first to give a more adult sensibility to Alice, along with adding more contemporary notes of whimsy.

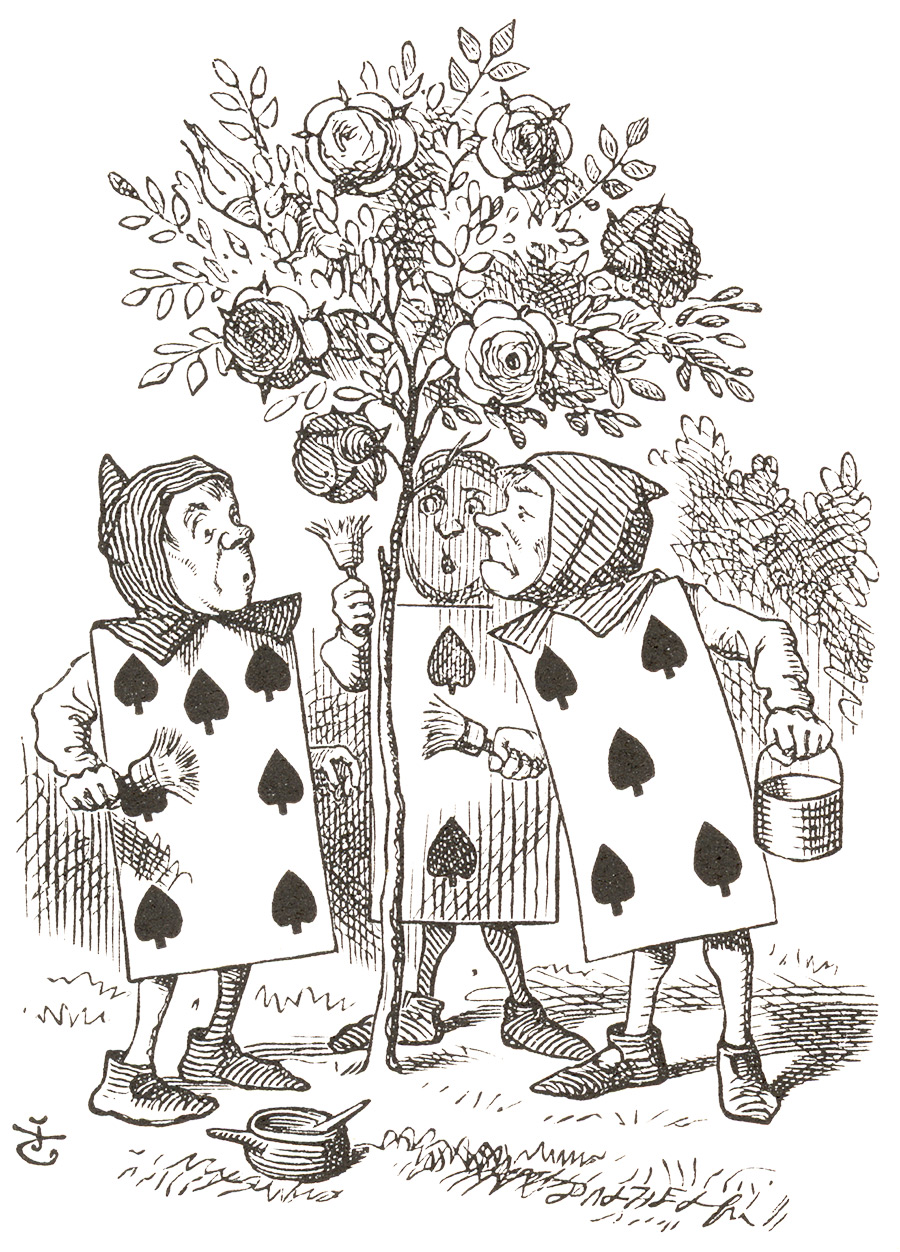

Alice scholars Zoe Jaques and Eugene Giddens noted, “The cards in the Pogány edition are reflective of several contemporary cultural reference points: the clubs appear as West Point cadets, the diamonds and hearts straight from the Ziegfield Follies chorus line, and the spades are members of the painters’ and decorators’ union.”