Rise of the Rail Splitter

The second child of Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln was born on 12 February 1809 in Hardin (now LaRue) County, Kentucky. When Abraham was seven years old, the Lincoln family moved to southern Indiana in search of better farm land and economic opportunity.

In 1818, almost two years after settling on the Indiana frontier, Abraham's mother died from a disease called the "milk sickness." A year later Abraham gained a stepmother when his father married a widow named Sarah Bush Johnston. After living thirteen years in Indiana, the Lincoln family, in another quest to improve its economic prospects, moved to Macon County, Illinois.

Lincoln worked hard to overcome his humble upbringing. Self-conscious of his lowly beginnings and lack of formal education, which he estimated totaled less than a year in length, Lincoln dedicated himself to a regimen of self-improvement, spending as much time as he could enhancing his reading and writing skills. The man who would later become one of this country’s most respected orators and writers did not learn the fundamentals of grammar until he was in his early twenties.

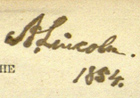

In 1830, at the age of twenty-one, Lincoln left the family farm to strike out on his own, moving to New Salem, Illinois, where he spent the next six years trying his hand at various occupations, including store clerk, mill hand, postmaster, and surveyor. Lincoln also served as a captain in the Black Hawk War for several months in 1832, though he was never involved in combat. It was during his New Salem years, however, that Lincoln developed an interest in politics. He was attracted to the Whig party and its leader, Henry Clay, who espoused government support for internal improvements, education, a central banking system, and protective tariffs. Such policies conformed to Lincoln's emerging view that government should create opportunity for economic independence for those, like himself, who were willing to work for it. After failing in his first attempt to gain a seat in the Illinois legislature in 1832, Lincoln was elected two years later and served four consecutive terms. In 1837, Lincoln issued his first public statement on slavery when he voted against several resolutions that condemned abolition societies. Although Lincoln was not a supporter of abolitionism, he believed strongly that slavery was "founded on both injustice and bad policy." Around this time Lincoln began to study law, which he saw as a way to economic security and a political career. He received his license to practice in 1836.

In 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield, Illinois' capital city, where he would reside until he assumed the presidency in 1861. It was in Springfield that Lincoln established a successful law practice and achieved political fame. It was in this city that Lincoln met and in 1842 married Kentucky-born Mary Todd, and together over the next decade they celebrated the birth of four sons, Robert Todd (1843), Edward (Eddie) Baker (1846), William (Willie) Wallace (1850), and Thomas or Tad (1853). In 1850, three-year-old Eddie died of pulmonary tuberculosis.

After winning the Whig Party's nomination to represent Illinois' Seventh District in May 1846, Lincoln was elected to his only term in Congress in August 1846. Lincoln's term began in December 1847 and he wasted little time in attacking President James Knox Polk’s 1846 decision to go to war with Mexico. Like many Illinois Whigs, Lincoln opposed the conflict, asserting that Polk waged war for land for the expansion of slavery rather than against an invasion of American territory, as the president had argued. The Mexican War was popular in Lincoln's congressional district, as it was in the country at large, and he probably would have been defeated for re-election had he not agreed to step aside for another Whig candidate. Before he left Congress, Lincoln introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia (he failed to get the votes needed to pass the legislation) and supported the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico. Disillusioned with politics, Lincoln spent the next five years practicing law.

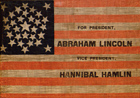

It was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 that drew Lincoln back into the political arena. Written largely by Stephen A. Douglas, Democratic senator from Illinois, the legislation repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had banned slavery above the Mason-Dixon Line and allowed residents of territories and future states to decide the slavery issue for themselves. The political turmoil engendered by this controversial act destroyed the Whig Party, divided Democrats, led to the formation of the Republican Party, and renewed sectional animosity by making slavery the predominant national political issue. Though he had hoped to keep the Whig Party intact, Lincoln soon became a leader of the Republican Party, which comprised various "anti-Nebraska" groups that opposed the spread of slavery outside of the Southern states where it already existed. Lincoln emerged as Douglas's most vocal critic in Illinois and in 1858 was nominated by the state Republican Party to challenge Douglas for his Senate seat. The election was notable for the series of seven debates covered by newspapers across the North. Although Lincoln lost the election (his party won the popular vote, but the election was at that time decided by the state legislature, which was controlled by the Democratic Party), his performance in the debates enhanced his national reputation to the point that he was touted by Illinois Republicans as a potential candidate for president in 1860. On 9 May 1860 the Illinois Republican Convention endorsed Lincoln for the presidency, anointing him as the "Rail Candidate," a homespun nickname that recalled his prowess with an axe during his prairie youth (the nickname later evolved into the “Rail Splitter”). Nine days later, Lincoln received the presidential nomination of the national Republican Party at its convention in Chicago.