Murder & Memory

The Civil War took an emotional and physical toll on Abraham and Mary Lincoln. By the end of the conflict, Lincoln looked much older than his 56 years. Mary Lincoln, who never fully recovered from the death of their son Willie in 1862, was ridiculed by the Northern press for her lavish spending during wartime and endured a whispering campaign that alleged that she was a Confederate sympathizer.

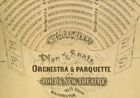

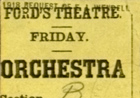

Moreover, in July 1863, she had suffered a serious head injury in a carriage accident. The Lincolns looked forward to putting the strain of the war behind them and to enjoying national peace and reunion, not to mention badly needed rest and relaxation. On Good Friday, 14 April 1865, the Lincolns attended Ford’s Theatre to see the comedy Our American Cousin. The crowd who joined the Lincolns for an evening of entertainment had no idea that they were about to witness one of the most tragic events in American history.

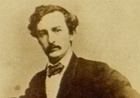

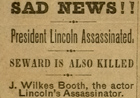

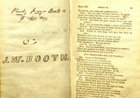

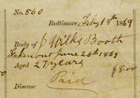

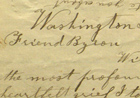

Among those who entered Ford’s Theatre on that Good Friday evening was the dashing twenty-six-year-old actor John Wilkes Booth. Born in Maryland and a member of a family of distinguished actors, Booth was a passionate advocate of the Southern cause. During the last years of the war Booth devoted more of his time to aiding the Confederacy as a smuggler and a spy than to acting. Sometime in late 1864, Booth devised a scheme to kidnap President Lincoln, whom he held responsible for the war, and hold him hostage in exchange for Confederate prisoners. Over the next few months Booth assembled a cohort of Maryland friends and Confederate sympathizers to assist with the kidnapping. When the plan collapsed, Booth, desperate in the midst of the Confederacy’s downfall, decided to assassinate Lincoln while two of his followers, George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell, were to murder Vice President Johnson and Secretary of State Seward. Sometime after 10 p.m. on Friday, 14 April, Booth, armed with a dagger and a pistol, entered the presidential box and shot the president in the back of the head and stabbed Major John Rathbone, one of the Lincolns’ guests. Booth leaped from the box to the stage, breaking his leg in the fall, shouting “Sic semper tyrannis” (thus always to tyrants) as he escaped from the theater. Lincoln, who never regained consciousness, was carried across the street to a boarding house owned by William Petersen. He died at 7:22 the next morning.

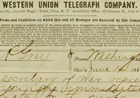

Within days of Lincoln’s assassination, most of Booth’s associates, including Atzerodt (who left town without even attempting to kill the vice president) and Powell (who severely wounded Secretary Seward), were arrested. Booth, who fled south from Washington and was soon joined by another associate, David Herold, led federal authorities on a twelve-day manhunt through Maryland and Virginia. In the early morning hours of 26 April, while sleeping in a tobacco barn on the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett, Booth and Herold were surrounded by Union cavalry. Herold gave himself up when ordered to surrender, but Booth refused, whereupon the soldiers set fire to the barn in order to force him out. As the fire raged, Booth was shot and mortally wounded by Sergeant Boston Corbett. Booth’s body was taken back to the capital and buried on the grounds of the Washington Arsenal, where Herold and the other suspected co-conspirators would soon be moved and held for trial. The trial, by military commission, lasted from 10 May to 30 June 1865 and resulted in a guilty verdict of conspiring with the Confederate government to assassinate the president, vice president, secretary of state, and General Grant. Four of the eight co-defendants, Herold, Powell, Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt (owner of the Washington boarding house where Booth and his associates frequently met), were sentenced to hang, three were sentenced to life in prison at hard labor, and one was given six months at hard labor. Although there was a move by several members of the commission to commute Mrs. Surratt’s sentence to life imprisonment, President Johnson denied the request. Mrs. Surratt, along with Herold, Powell, and Atzerodt, was hung on 7 July 1865, the first woman to be executed by the United States government.

The celebratory mood that pervaded the North in the wake of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox was shattered by Lincoln’s assassination and replaced by profound grief. Lincoln’s body went on view at the White House and the Capitol, where it was seen by thousands of mourners. Lincoln’s funeral was held in Washington on 19 April; two days later the funeral train left Washington and embarked on a twelve-day journey to Springfield, Illinois, the martyred president’s final resting place. The train stopped in eleven cities and passed through many small towns, and was witnessed by hundreds of thousands of Americans who wished to pay their last respects. On 4 May 1865 Lincoln was buried in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery.

It was during the period of national mourning that Lincoln’s standing changed from an often unpopular and controversial president to a figure of iconic proportions. In the weeks and months following his death, Lincoln the man and the president was praised by supporters and critics alike in sermons, speeches, and newspaper editorials. From the moment of his untimely death to the present, Lincoln’s exalted status as the president who won the Civil War, ended slavery, and preserved democracy has remained constant. There have been more books and articles written about Lincoln than any other American, with many publications planned during this bicentennial year. There have been almost as many Lincoln collectors as books published about our sixteenth president. The field of Lincoln collecting began with the assassination, as Lincoln’s friends, acquaintances, and contemporaries sought out objects and relics associated with the late president. In the half century following the assassination, it seemed like almost everyone was collecting Lincoln. Today, in the wake of the bicentennial of the man whom many consider as this country’s greatest president, Lincoln’s deeds and words continue to inspire and uplift people from all walks of life and all parts of the globe.