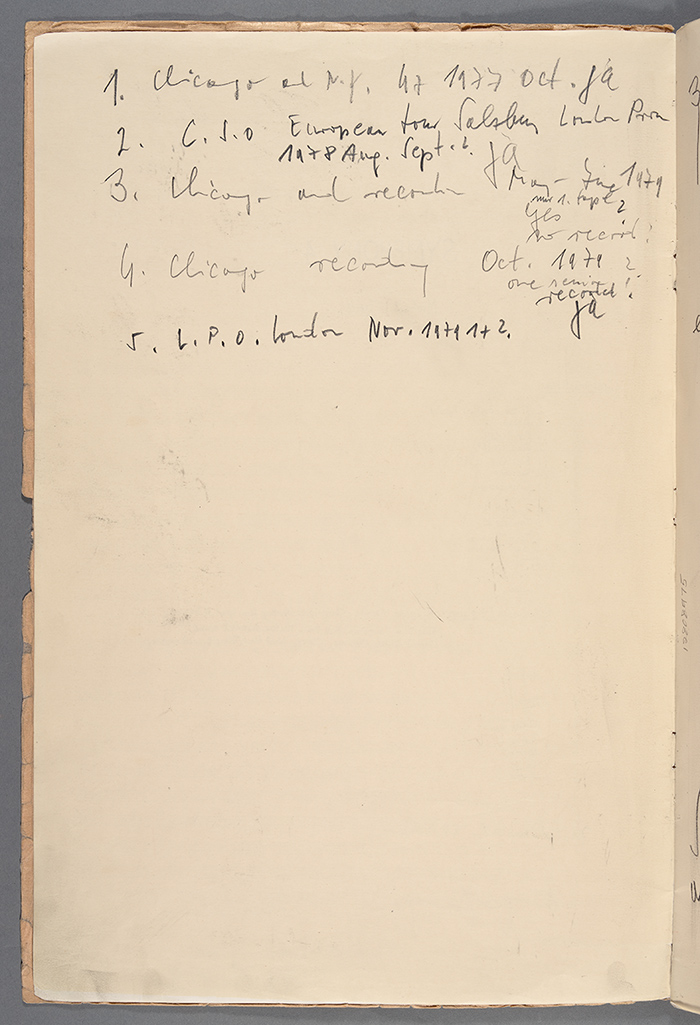

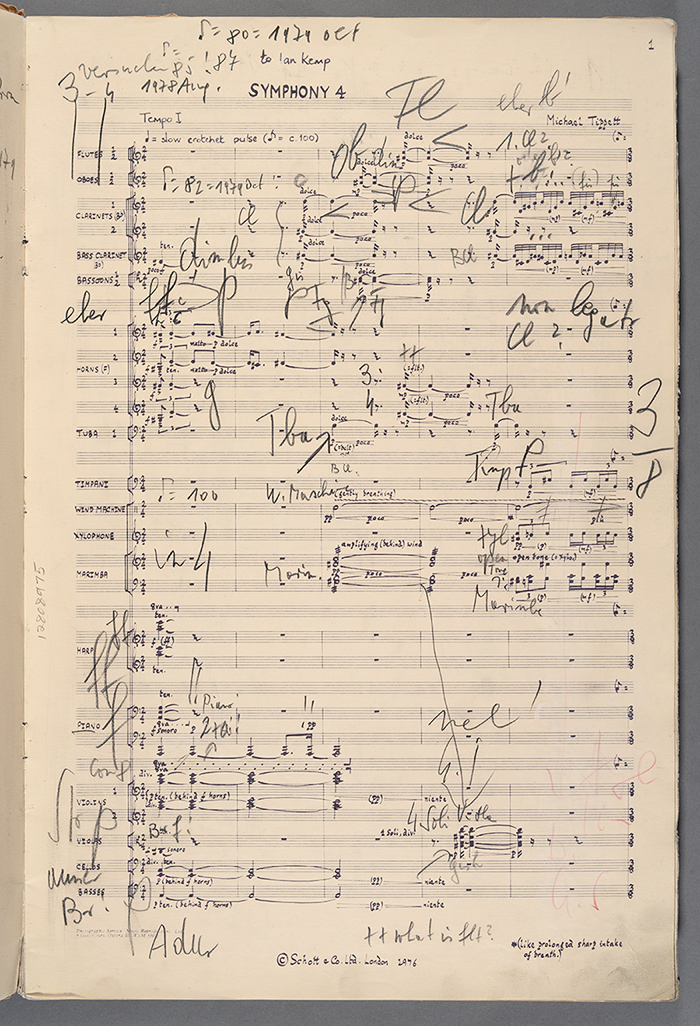

Solti, a self-declared “antifascist, antinationalist, antimilitarist” (Memoirs, 11), must have shared some common ground with Sir Michael Tippett, who was an outspoken pacifist. Both men were knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, Tippett in 1966 and Solti in 1971. Perhaps it was partially in gratitude to his adopted country that Solti (born a Hungarian citizen) helped to further the cause of British music by commissioning a work from Tippett. “Listening to Solti rehearse … with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, I was almost unable to concentrate on the music being played; what set me off was the wondrous range of orchestral colors being deployed […]” (Tippett on Music, 107). Written with Solti’s orchestra in mind, the work is scored for a large ensemble, expanded to include six horns, two tubas, and a large percussion battery. Solti conducted the premiere of Tippett’s final symphony in Orchestra Hall, Chicago, on 6 October 1977. According to the composer, the symphony itself is a “birth to death” narrative. Its program is announced by breathing sounds at the beginning and a final exhalation at the end. Its theme could tip toward resignation but does not. Instead, it is a celebration of life and an acceptance of its inevitable conclusion.

Sir Michael Tippett. Symphony no. 4: Tempo 1. Perf. Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Recorded at Medinah Temple, Chicago, October 1979 (London 433 668-2). Record Collection CD 10199

http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/002834255/catalog