Introduction

“Life is in the transitions as much as in the terms connected; often, indeed, it seems to be there

more emphatically, as if our spurts and sallies forward were the real firing-line of the battle, were like the thin line of flame advancing across the dry autumnal field which the farmer proceeds to burn.”

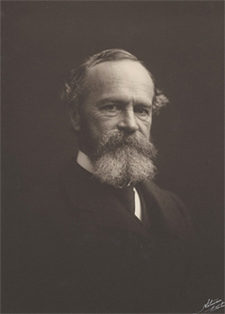

--William James, “A World of Pure Experience” (1904)

One hundred years after William James’s death, the Houghton Library, drawing upon its vast archive of James material, looks back at transitional moments of his life: his vocational dilemmas, spiritual crises, professional paths, and brave philosophical sallies forward. In these transitions, we can see the “plural facts” of James’s experiences, his public and private battles, and elements of what he called the “mosaic philosophy” of radical empiricism, pragmatism, and pluralism.

William James was born in New York City in 1842, the first child of Henry and Mary James. He had four siblings: Henry, Jr. (b. 1843), who became an internationally-lauded writer; Garth Wilkinson (b. 1845); Robertson (b. 1846); and Alice (b. 1848), noted as a diarist. The James children had a peripatetic education in America and Europe, depending on their father’s quirky educational views, sometimes attending schools, sometimes tutored at home. The family lived for a time in Newport, Rhode Island and finally settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

When William James died in August 1910, he had attained international prominence as the founder of American psychology and as a philosopher. He could look back on a long and successful career as a Harvard professor. He was a husband and father. These roles were not inevitable. He might have been an artist, like his contemporaries John Singer Sargent and William Hunt. He might have practiced medicine; or followed in the footsteps of his teacher Jeffries Wyman and devoted himself to physiology; or joined the ranks of eminent nineteenth-century naturalists, such as Louis Agassiz. When he first took a teaching position at Harvard, he had no intention of making college teaching a career, and even when he started down that path, he might easily have ended up at Johns Hopkins, where he once coveted a position.

James’s life was punctuated by decisive moments when he might have taken one path or another; when, as he once told Alice Howe Gibbens during their protracted courtship, he had to decide on his vote for the kind of world he wanted to create for himself, and for the kind of man he wanted to be. Sometimes, those moments did feel like a battle – against his father, who opposed his interest in art; against his own self-image as a sickly man; against rationalism, determinism, monism; against elitism and war-mongering.

This exhibition reveals some of the intellectual tensions that gave rise to his most famous works: The Varieties of Religious Experience, Pragmatism, and A Pluralistic Universe. In his celebration of novelty, his warm tolerance of all manner of spiritual experience, his championing of multiple perspectives for apprehending reality, James stood apart from many of his contemporaries. He meant his ideas to offer a process of making sense of experience, of justifying decisions that take account of a thinker’s desires and needs, and of accounting for one’s own presence in the world.

An individual’s philosophy, James wrote, “is itself an intimate part of the universe, and may be a part momentous enough to give a different turn to what the other parts signify.” Now, in the 21st century, James’s works endure, still vital, sympathetic, brilliant, and passionate.

An exhibition such as this requires a number of people to make it happen. Thanks are due first, and foremost, to the James family, whose extraordinary generosity in donating William James’s library and papers to Harvard over the years has made not only this exhibition possible, but also ensured that William James’s legacy will endure. All material exhibited here, unless otherwise noted, is their gift. The William James Lecture Fund on Religious Experience at the Harvard Divinity School funded the research for the exhibition; my particular thanks to David Lamberth. Other Harvard archives lent material to complement the Houghton holdings: thanks to Robin McElheny of the Harvard University Archives; Jack Eckert of the Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library, Harvard Medical School; and Connie Rinaldo and Robert Young of the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology for their assistance. Carie McGinnis, Mary Oey, and Susi Barbarossa of Houghton Library, and their colleagues at the Weissman Preservation Center, prepared and installed the items in the cases.

For the web exhibition that expands on the items here in the cases, my thanks to Enrique Diaz, Leslie Morris, Heather Cole, and Taylor Ferracane for their help in bringing this exhibition to those who cannot travel to Cambridge. Dennis Marnon facilitated the publication of the essays about this exhibition published in the Harvard Library Bulletin. Leslie Morris, the curator of the James papers, did much behind-the-scenes work to help everything come together.

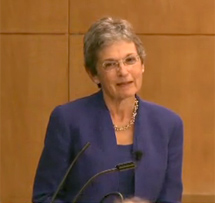

--Linda Simon, curator; Professor of English, Skidmore College; General Editor of William James Studies; and author of Genuine Reality: A Life of William James (1998).

“Life is in the transitions”: William James, 1842-1910, is complemented by “William James in His Times and Ours: Essays on the Occasion of the Centennial Exhibition at Houghton Library” in the Harvard Library Bulletin (Summer 2009). Essays by twelve leading intellectuals and scholars-- Drew Gilpin Faust, Susan Gunter, Edward Hoagland, David Lamberth, Louis Menand, Steven Pinker, David S. Reynolds, Michael James, Jean Strouse, Colm Tóibin, Gore Vidal, and Cornel West—think about key items in the exhibition from their own perspectives. Copies of the Bulletin are available for purchase at $15; orders should be addressed to Monique Duhaime, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138.