By Kyle Courtney — attorney, Harvard Library copyright advisor, and founder of Fair Use Week.

February 21–25, 2022 is the ninth annual International Fair Use Week — celebrated at libraries, archives, museums and other institutions around the world in recognition of an element of copyright law critical to research, education and scholarship.

Without fair use, scholars would be unable to quote from sources; journalism would be unable to produce articles; thesis and dissertation writers would be unable to offer criticism or analysis of other works; professors would be unable to use music or film in classrooms; libraries would be unable to digitize their print materials — the list of necessary actions that would be affected goes on and on.

What Is Fair Use?

Fair use (known as “fair dealing” in Canada and other jurisdictions) is an essential limitation and exception to copyright, allowing various uses of copyrighted materials, under certain circumstances, without permission or payment to the copyright holder.

Copyright law grants copyright holders a bundle of exclusive rights — including the rights to reproduce, perform publicly, display publicly, prepare derivative works of, and distribute copies of the copyrighted work. But despite these exclusive rights, copyright law recognizes an essential need for “breathing space.” This space allows another user to harness some of the copyrighted work without permission, “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching…scholarship, or research….” This is what is known as fair use.

Fair use allows for uses that (as the US Constitution says) “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” and preserves, without infringement, the values also enshrined in the First Amendment. Fair use is also designed to be flexible, which allows copyright law to adopt to new and changing technologies.

To determine whether fair use applies, there is a four-factor test that can be used. The four factors are:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is commercial or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work, including whether it’s published or unpublished;

- the amount used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

See this infographic for a more detailed explanation of fair use and of the four factors.

What Is Fair Use Week?

Fair Use Week (now also celebrated internationally as Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week) is a great example of successful grassroots organizing by cultural institutions, including libraries, archives, museums, and other institutions, to celebrate this most critical of copyright topics. And the first full Fair Use Week celebration, in 2014, launched here at Harvard Library!

Every year, participating organizations use the week to celebrate, educate, inform and promote the important doctrines of fair use and fair dealing. Institutions can participate in ways from social media engagement (e.g., tweets and blog posts), to the creation of resources (e.g., infographics and comic books) and multimedia content (e.g., podcasts), to live engagement (e.g., panel discussions or lectures).

Each Fair Use Week’s content is continually accessible, so, even after the celebration ends, librarians, educators and advocates can continue to promote the doctrines of fair use and fair dealing.

Fair Use and Libraries

As the fair use language suggests, the right of fair use is a natural ally of library-related work: libraries often provide all types of materials to patrons for uses such as “criticism, comment, teaching, scholarship, and research.”

In the library context, the four-factor test is also used up front for risk mitigation. For example, libraries frequently use the fair use statute to determine whether or not they can perform a certain activity or function involving copying or scanning. By reviewing the four factors, as a court might, a librarian can determine whether the action she is taking might risk infringement, or falls squarely within the realm of fair use. Increasingly, libraries and archives themselves engage in fair uses of their own materials — from digitization to text mining, from online collections to digital exhibitions, and more.

In recent years, US courts have focused increasingly on whether an alleged fair use is “transformative.” A work is transformative if, in the words of the Supreme Court, it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” Use of a quotation from an earlier work in a critical essay to illustrate the essayist’s argument is a classic example of transformative use. Conversely, a use that supplants or substitutes for the original work is far less likely to be deemed a fair use than one that makes a new contribution.

In the last decade, there were some enormously positive developments in the realm of copyright, transformative fair use, and libraries. The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the ruling in Authors Guild v. HathiTrust, deciding that providing a full-text search database of scanned books is the same as providing access to these books for people with print disabilities, which constitutes a transformative fair use. HathiTrust has paved the way for university libraries to embrace other activities, such as text and data mining, which are now on the forefront of interdisciplinary research.

A similar case, Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc., found that Google did not infringe any copyright through its Google Book Search database, which shows “snippets” or significantly small portions of works from the millions of books that were scanned at many US university libraries. US Circuit Judge Denny Chin dismissed the lawsuit and affirmed that the Google Books program meets all legal requirements for fair use.

These laws and cases reveal the beneficial nature of having continual fair use programming at every library, archive, museum, and other cultural institutions. By investing in such efforts, patrons at each institution will be better informed and will fully understand the benefits that fair use grants, allowing for more creative use and reuse of work.

Harvard Library and Fair Use

Harvard Library’s Office for Scholarly Communication (OSC) founded the first week-long celebration of fair use in 2014. As it was my first year as Copyright Advisor, in a new position, I was looking for something big to accomplish. The idea for a celebration was posted on the Fair Use Allies listserv by Prof. Pia Hunter, now Teaching Associate Professor at University of Illinois College of Law. That very year, Prof. Hunter bought the website fairuseweek.org ahead of the annual celebration. In the second year of Fair Use Week the site went live, and, now run by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), it continues to serve as the central spot for covering all things Fair Use Week.

At the fifth anniversary of Fair Use Week conference, it was my pleasure to award Prof. Hunter the Fair Use Week Founders Award, given to her "for the highest level of dedication in the service of Fair Use Week including the great achievement in the vision for Fair Use Week & as a true friend, scholar, & leader in the promotion of fair use.”

But Harvard Library’s connections to fair use go much further back than the now-annual celebration — all the way back to its beginnings. As illustrated in OSC’s Fair Use Week comic, Harvard Library has an important tie to the history and development of fair use in the United States, in a case involving former Harvard librarians, Harvard deans, Harvard professors, and Harvard alums.

Jared Sparks, the first McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History at Harvard (and later President of Harvard College), was the proprietor of President Washington's public and private letters. In 1837, he edited these letters, added notes and illustrations, and wrote an original biography. Charles Folsom, former Harvard Librarian, then published this work as The Writings of George Washington in 12 volumes totaling 7,000 pages.

In 1841, Rev. Charles Upham, Harvard Class of 1821, a historian and anthologist, published a two-volume, 866-page work entitled The Life of Washington in the Form of an Autobiography with another Boston publisher, Bela Marsh.

Sparks and Folsom sued Upham and Marsh for "piracy of the copyright." They claimed that Upham and Marsh had copied nearly 400 pages verbatim out of Sparks' collection.

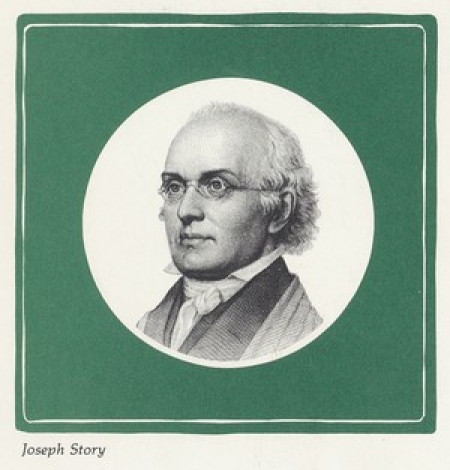

This case, Folsom v. Marsh, was the first fair use case in the United States. And it was heard in front of Justice Joseph Story, then Justice of the US Supreme Court, a Circuit Court judge for Massachusetts, Harvard Law School Dane Professor, and already a legendary jurist in American law.

It was Justice Story who, adapting English law, foreshadowed the future of fair use opinions in this case. Justice Story’s writing, which created this four-factor balancing test — balancing the copyright holder’s rights and a user’s fair use — is now embodied in US copyright law.

Using this four-factor test, Justice Story deemed the Upham and Marsh work as simply clever “use of the scissors” — borrowing too much of the original, which affected the sale of the original work — and found them guilty of copyright infringement. This was despite Justice Story’s appreciation of the “very meritorious labors of the defendants, in their great undertaking of a series of work adapted to school libraries.”

Happy Fair Use Week!

Copyright law affects the work of librarians every day. In fact, I like to say that “every day is Fair Use Day” in a modern, 21st-century library. The majority of librarians' work deals with accessing, storing, exhibiting, or providing access to copyrighted material.

This year, with help from our partners worldwide and the Association of Research Libraries, we are continuing the conversation we started in 2014, and exploring fair use’s aspects through panels, blog posts, workshops, fair users’ stories, and a little bit of fun. Please follow the activities online at fairuseweek.org, look for guest fair use expert blogs hosted by the OSC, and follow Twitter @FairUseWeek to get in on the fair use fun!