In the Early Modern period, broadsides were the most common form of printed material. These single sheets of text could be produced quickly and cheaply, and were thus the ideal media for many purposes, including advertisement, entertainment, propaganda, and the dissemination of local and national news.

At a penny apiece, even the poorest could afford them. They were passed around among neighbors and pasted on walls as economical decoration.

During the 1660s, when broadside production was at its peak, print shops in London and the other large cities of Britain churned out over 400,000 copies a year.

Such documents were not designed to last. Despite their immense popularity, therefore, relatively few survive today. Many of the titles in Houghton Library’s large broadsides collection are very rare, some existing only in a single remaining copy.

Over the years, Houghton has acquired several significant groups of broadsides amassed by individual collectors. Three of them, the Bute, Huth, and Percy collections, are particularly noteworthy.

The Bute Broadsides

John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, the third marquess of Bute (1847–1900), assembled his collection of broadsides around the year 1892. The collection was acquired in its entirety in 1951, thanks to a gift from Curt H. Reisinger. It comprises approximately 500 broadsides, each inlaid or pasted in one of five large portfolios.

The contents are arranged in a rough chronological sequence, beginning with several pre-1600 copies. The vast majority of the broadsides date from the 17th century, although there are a few 18th-century sheets as well.

The subjects treated are wildly variable. Some are not especially topical: they include astrological tables, guides to Scripture, advertisements for elixirs, and reports of unusual or monstrous animals. Others more closely reflect changing political, economic and social concerns. Multiple statements of grievance from Quakers reveal the struggles of the minority religious sect. The evils of “popery” were a perennially popular subject, and tracts from the late 1700s describe battles between government forces and the Jacobite rebels. Around a dozen broadsides are devoted to the plague of 1665.

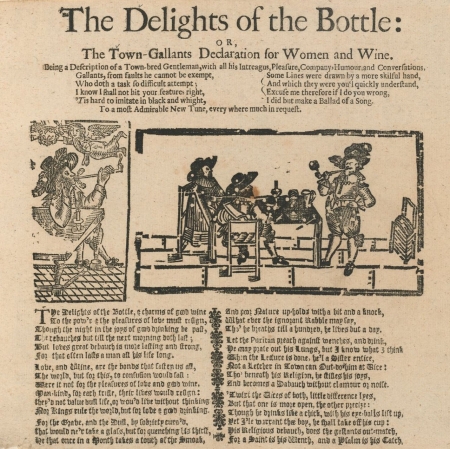

The tone of these texts ranges from very earnest (in the case of the more pious works) to scathingly satirical. What they almost all share in common is a presentation designed to catch the eye. Printers frequently used a variety of typefaces on a single page, and the text is almost always paired with two to five woodcut illustrations. These were sometimes made specifically to accompany an announcement, but more often chosen from a set of stock illustrations.

The Huth Broadsides

Houghton holds two volumes of broadsides from the library of Henry Huth (1815–1878) and his son Alfred (1850–1910).

Whereas the Bute broadsides are mostly prose pieces, the Huth broadsides (around 320 in all) are all ballads. A ballad broadside typically features a set of lyrics, several illustrations, and an indication of the tune to which it is sung. Ballad broadsides formed an important link between the oral popular music tradition and the new era of printed communication. Sold in stalls and by peddlers who would advertise their wares in song, they provided fodder for performances in all sorts of venues, from pubs to manor houses.

The Huth broadsides are almost all from the 17th century, the heyday of the British ballad, and are printed in the black-letter (gothic) typeface that had otherwise all but gone out of use at that time.

Dominant themes include infidelity, doomed romance, and clever deceits. Many are laden with sexual innuendo, and very few could be described as pious. A number of them explicitly reference historic events, such as the exploits of the Scottish folk hero John Armstrong, the struggles of the royal rebel James, Duke of Monmouth, and the execution of Charles I.

The Percy Broadsides

Thomas Percy, Bishop of Dromore (1729–1811), didn't simply collect ballad broadsides; he was a crucial figure in preserving the history of the ballad form through his 1765 publication of Reliques of Ancient English Poetry.

This work, a collection of ballads that greatly influenced Burns, Coleridge, and Wordsworth, was based primarily on a manuscript folio now in the British Library. However, Percy also drew from printed broadsides, and 321 of his broadsides are now at Houghton, along with six boxes of transcriptions and correspondence related to the collection.

Most of Percy’s broadsides were published in the second half of the 18th century, and there are several interesting differences between them and the earlier ballad broadsides of the Huth collection. For one thing, the Percy broadsides are almost all printed in roman type, a form closer to the typefaces in use today. For another, many of the Percy broadsides were printed by the Dicey family, who introduced a number of innovations to ballad preparation and marketing. One such novelty was the insertion of a preamble that purported to “give insight into…the time when such songs were made.” Such introductions tended to present the ballads as nostalgic relics from a simpler time.

Finally, many of the Percy broadsides bear his editorial marks, and so help to reveal how the Reliques was composed.

Accessing These Materials

Access to original copies of the broadsides in these collections requires permission of the curator, due to their fragility, but digital and/or microform reproductions are available for most of the broadsides.

The Bute broadsides can be browsed in HOLLIS.

Digital versions of the Huth broadsides are available via HOLLIS, under the call number EBB65H.

Thomas Percy’s broadsides may be found under the call number EB75 P4128c.

The Harvard Law School Library has a fully digitized collection of British crime broadsides, described here.

Houghton is part of the English Broadside Ballad Archive digitization project.