Cyanotypes were invented in 1842 and continue to be used today. The beautiful blue prints evolved from a formal printing technique in the 19th century to a more experimental and process driven approach in the 20th and 21st centuries. The shadow prints are created by putting a transparent photo negative or other object of interest (plants are common) on light sensitive paper and then leaving it in the sun for a set amount of time–the longer the darker the blue becomes. The covered areas remain white and the exposed sections become blue, evidence of the sun’s touch.

On rotating display:

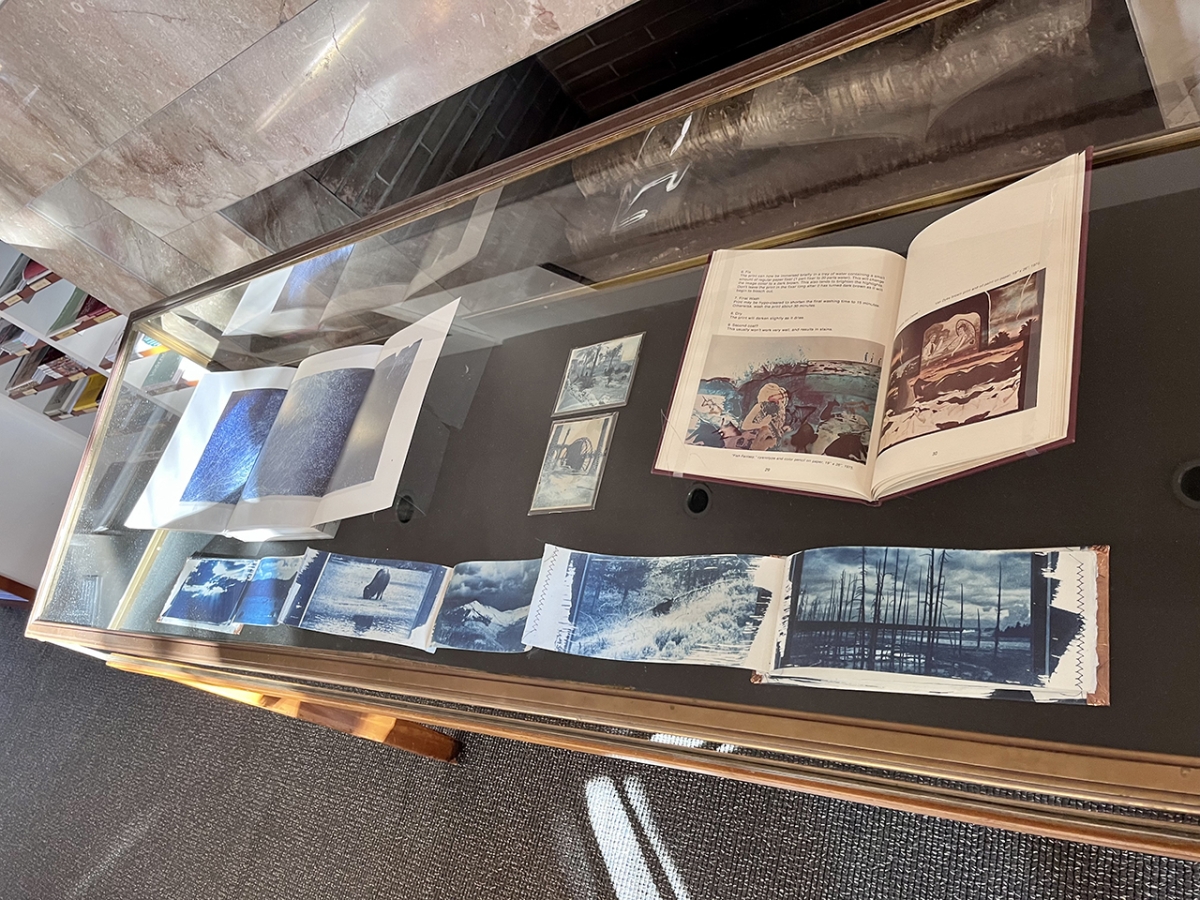

Meghann Riepenhoff, Littoral drift: Ecotone, 2018.

The series consists of cyanotypes made directly in the landscape, where elements like precipitation, waves, wind, and sediment physically etch into the photochemistry.

HOLLIS: 99153722703803941

Images of Iraq by John Henry Haynes, circa 1888-1900. Cyanotype. John Henry Haynes Archive, Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University.

HOLLIS: 990121056480203941

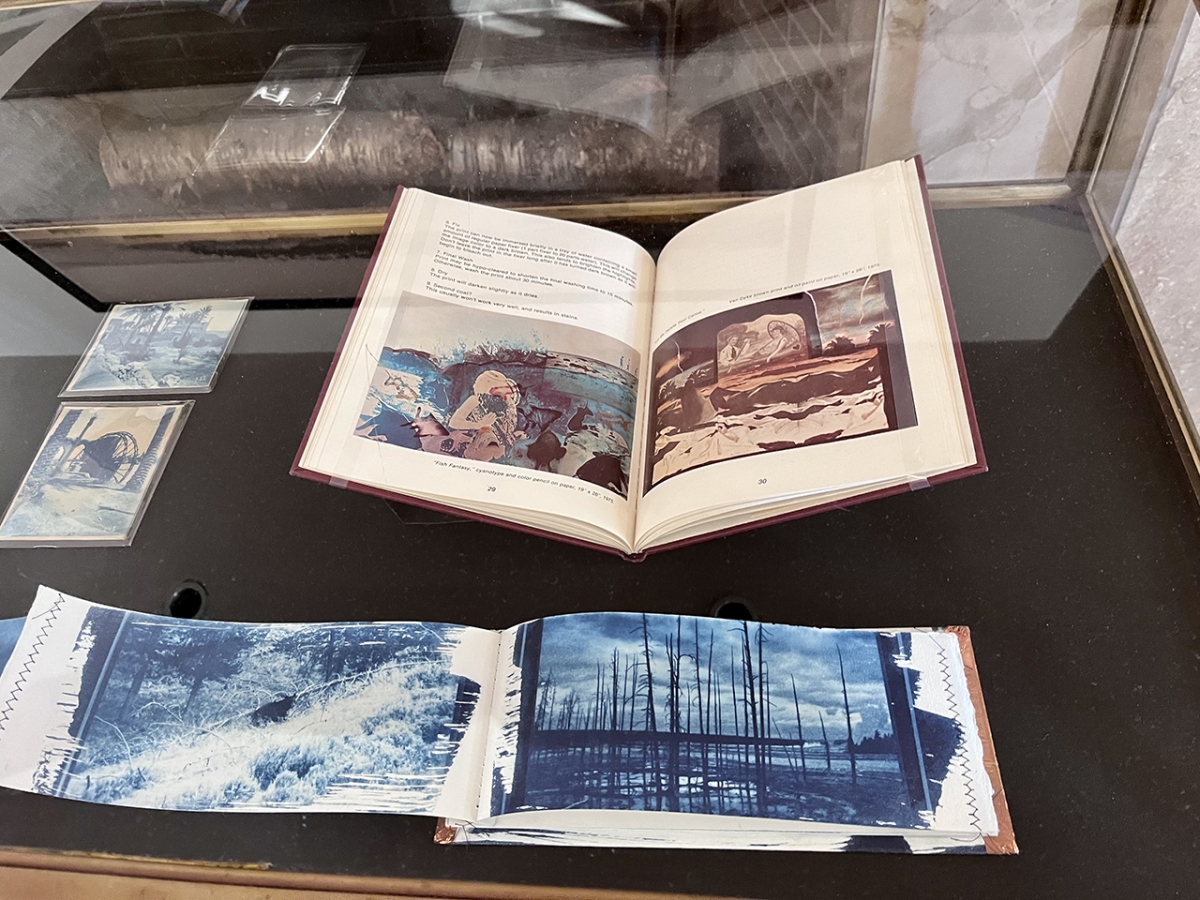

Bea Nettles, Breaking the Rules: A Photo Media Cookbook, 1977.

Based on photography workshops Bea Nettles gave across the US, the how-to book is a step-by-step guide to alternative photo processing. “Fish Fantasy” is a cyanotype with colored pencil etching, a lovely example of the experimental process displayed throughout her “recipe” book.

HOLLIS: 990082327190203941

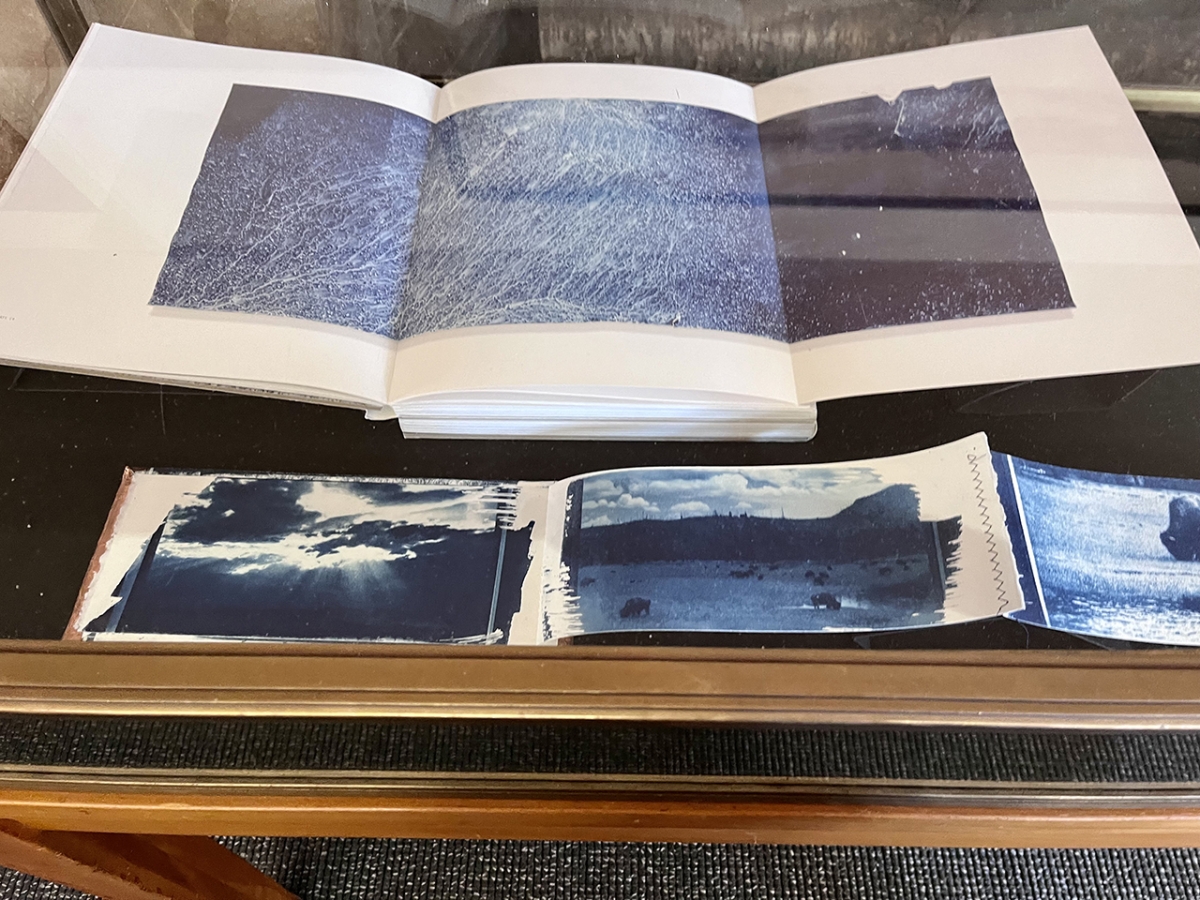

Ginger Burrell, Yellowstone, 2009.

Accordion book of landscape images in Yellowstone National Park. The cyanotypes are printed on Rives BFK.

HOLLIS: 99156846780703941

Emily Sheffer, Winter Solstice, 2017.

The accordion book consists of a cyanotype from every hour of sunlight on the winter solstice.

HOLLIS: 99156550066603941

Guest curated by Lucy Jackson (‘23)